Submitted by A.B. Youngman on Fri, 10/11/2023 - 16:53

This event was part of our occasional online Food for Thought panel discussion series. You can watch the recording here, or read the report below for the main points:

Professor Howard Griffiths, Dept of Plant Sciences, University of Cambridge, our excellent chair, started the event by inviting each of our expert panellists to answer the title question: How low can you go: can food production reach net zero?

Dr Sophie Attwood, World Resources Institute: to stand a chance of net zero by 2050, or of even getting close to it, much more action is needed, much more quickly and, crucially, all concerned, particularly governments and scientists, need to do a better job of getting a clear message out.

Dr Adam Pellegrini, Associate Professor, Dept of Plant Sciences, University of Cambridge: the policies to promote regenerative farming that governments are beginning to roll out; they really need to clarify what they are promoting and by how much. While prospects seem bleak, there are opportunities, research on carbon dioxide removal is on-going but it requires much improvement.

Dr Emma Garnett Researcher in Health Behaviours, LEAP, University of Oxford: the main barrier to achieving net zero is a lack of political and societal will.

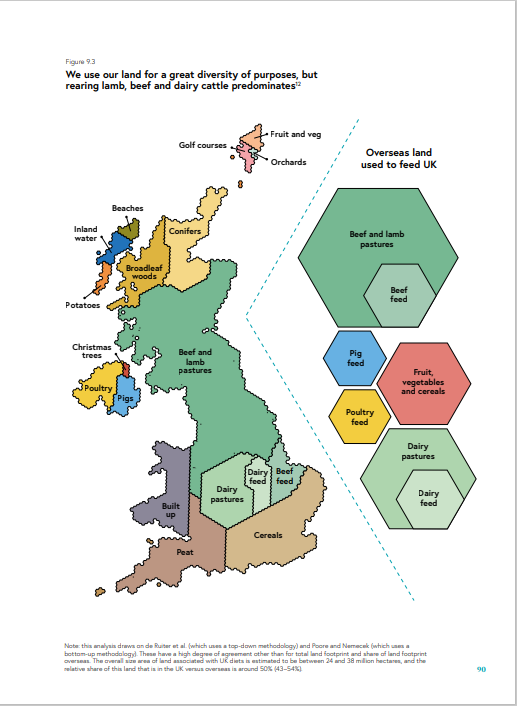

Professor Sarah Bridle, Chair in Food, Climate and Society, University of York: the best chance for the planet to reach net zero could be to reduce the amount of land used for animal feed. Currently about 80% of the land globally that's used for agriculture is used to produce food that's fed to animals. If humans ate more plants and fewer animals, more land could be used for sequestering carbon.

The session was then opened up to audience questions, the range of which was great and our panellists' answers fascinating and informative:

How can government policy and individuals contribute to getting food production to net zero, what would you recommend?

Dr Atwood: Businesses tend to have a longer term view than governments as they're planning for the next 10-20 years. They're concerned about the potentially catastrophic risks posed to the food system by climate collapse. Industries increasingly recognize the threat to their bottom line and so will increase pressure to adopt policies that will decrease these risks.

Dr Garnett: The big economic levers are really what we need, for example redirecting subsidies away from livestock, which is much more publicly acceptable than a meat tax, even though they have quite similar effects.

On an individual level we can all learn how to cook one or two really delicious vegan meals with plenty of protein, and share them with your friends.

Dr Pellegrini: Carbon tax. You can bring about major change when you turn the screws on something from the top down and potentially motivate big companies that manage suppliers to change who they're either sourcing from or what the supplier does, and thus reduce emissions.

Dr Attwood: Massively, increasing the availability of good quality, really tasty plant-based options; a carrot, not stick approach.

If you swamp people's choice environment with the thing you want them to choose, they will choose it.

This could translate to policy through a mandate on number of the ratio of vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes, or the number of days per week where meat could be sold in restaurants and food retailers.

On an individual level, if you are only going to do one thing, cut down the amount of beef and dairy that you eat. People don't like being told what to do, but seeing others modelling this behaviour is really influential. So cut the cut the cows and eat veggie in front of your friends!

Prof. Bridle: It doesn't have to be just a tax. It could be reducing existing subsidies to livestock production, but also subsidizing the healthy, sustainable choices with a revenue neutral tax.

Dr Garnett: Lobby local government and back candidates in elections who will take more measures. It is amazing how much a persistent individual can shift council policies.

Dr Attwood: Academics have a lot of amazing insights that would be much more likely to be adopted if only they were better communicated.

Prof Bridle: Funding agencies are starting to do more in terms of the way that they actually frame what is research and the way that they give out grants. But universities have some way to go as well in actually recognising their policy work, and not necessarily requiring, the sort of research paper that takes three years to write, a year in review and is then behind a paywall that is unfit for the purpose that we need to address.

What is regenerative farming, and could it help us achieve net zero? Are there other nature-based solutions to the net zero problem?

Dr Pellegrini explained regenerative farming and how the methods it involves may reduce carbon emissions, but warned that research shows that its efficacy is very dependent on context, so while regenerative agriculture is a useful concept helping find potential pathways to reduce emissions, the results are very variable.

Farming on peatlands is massively detrimental to the environment and releases a lot of greenhouse gas emissions Peatland restoration is actually one of the big nature based solutions that pretty unequivocally will be a net win for greenhouse gas emissions.

Can low- and middle-income countries afford to eat sustainably?

Dr Attwood: There has been a lot of debate around this recently in relation to the Eat Lancet Plantary Health Diet. Following that diet is probably unaffordable for people in poorer countries, but if, rather than following the Westernised patterns of eating that the Eat Lancet Diet proposes, recommendations for sustainable diets are culturally contextualized, it is possible for people in low-income countries to eat sustainably. India, for example, has very, very low meat consumption levels compared with the global average. It is a matter of promoting diets that are both culturally appropriate and nutritionally complete and that people have the skills to produce them.

Dr Garnett: The idea that sustainability is always more expensive is happily not true. Meat is more expensive than fruit and veg, and we would all be healthier if we ate more plants and fewer animals. The question is how do we scale up sustainable production of fruit and veg?

Does eating meat increase the amount of land needed for food production?

A significant amount of that is being used to produce cereals to feed to animals. Prof Bridle showed the illustration below, taken from the National Food Strategy.

Conclusions

Prof Griffiths thanked our excellent speakers and drew the event to a close with two final observations:

- One major plea from the panel is that, as scientists, we are not doing enough to educate, to promote or to provide outputs that are digestible (pun intended) for politicians and graspable by the general public, so that they can understand the simple and effective steps that could be taken. These are things that won't cost too much, but they will make a change; a slow but progressive step towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions and achieving net zero.

- The other clear challenge is that we must convince politicians to act; there will be an election in the next 15 months or so. Prof Griffiths urged audience members to use their votes, discuss these issues with politicians and ask them what their policies are, be it at a local or a national level. What would they espouse in order to bring about net zero? Do they recognise the challenge that climate change will bring to society as a whole? Not just in the UK. But globally as a whole.

Publications referred to by our speakers:

Home is Always Worth It. The first time I met what I have come… | by Mary Annaïse Heglar | Medium

Benton, T.G. Academics can do more to disrupt and reframe the solution space for food system transformation. Nat Food (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00876-w